Creativity in a World of AI

Unleashing Your Artistic Eye as a Superpower in This Brave New World

When I made the decision to become a 3D Artist, I dove right into learning the software. I got my hands on Cinema 4D and immersed myself in its world. I learned every button, mastered the terminology, and tinkered with all the settings to generate rendered images. And you know what I produced? A whole bunch of blah images.

So I started looking into it and quickly realized that most animation studios were using Maya. Ah-ha! There it was. It wasn't me; it was the software that was holding me back. How could I create professional-level work with a professional-level software package?

Once again, I jumped into learning all the buttons. And for Maya…there’s a lot to learn. Truthfully, all this stuff was confusing, frustrating, and, above all, time-consuming but, I was determined, and really focused on learning every nuance of the software. Eventually, the concepts started to make sense and I begin producing artwork. But alas, the results were still mediocre at best.

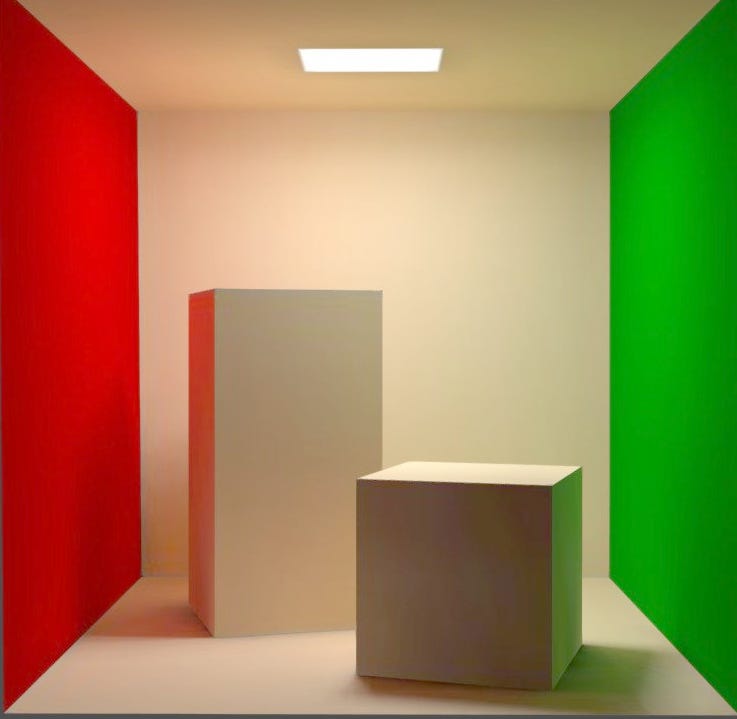

Then, one day, I saw a fellow classmate at SCAD who was better than me. What was her secret? Wait…what was she using. It was Maya but she also tapped into…Mental Ray! That had to be it! It wasn't me; it was the renderer. I needed to learn about final gather, global illumination, and that mysterious box with blue and red walls. That's the software that would make me a pro.

But guess what? I learned Mental Ray and you guessed it.

More disappointing artwork.

Okay, okay... what about compositing? I just needed to master Shake so I could take my lackluster images and transform them into professional-looking ones. And you guessed it...more average art.

At that point, I was about to wrap up my time at SCAD, and I was well-versed in various software. I had the desire to learn, but I still couldn't create the quality of work needed to be a professional artist. What was I missing?

My First Job in the Industry

Luckily for me, I landed a technical assistant job at Blue Sky. They didn't trust me with creating art, but my degree at least qualified me to make sure the render farm computers stayed on overnight.

And to be clear, that was totally fine with me. I saw this as an opportunity to take a little more time to figure things out. Perhaps, once and for all, I could discover what software I was missing. I knew Blue Sky had its own proprietary renderer, and it had to be more advanced than anything I had used in school. I mean, they were the big leagues, the pros. They used the best of the best.

Imagine my shock when I discovered that this proprietary renderer was even more basic than Cinema 4D. It didn't even have a user interface! Everything was done in a plain text document.

Let me emphasize that again... when the artists were positioning lights in a scene, they couldn't even see the scene. They did it all in a simple text document. Things like this:

Position = 27.2 41.4 91.5

Color = 1.0 0.6 0.7

Intensity = 2.3

Shadows = ON

Can you believe it? They lit all those breathtaking images for multiple films using nothing but a text editor. How were they able to create all those images, let alone the incredible ones I saw on the screen?

Well, it turns out that the software didn't realy matter. What truly mattered was having a pool of talented, dedicated artists who could craft stunning images. Sure, they needed to know the software, but it wasn't the main focus. They honed their skills in using color, light, and composition to create captivating images that evoked emotional reactions in the audience.

That was the magic sauce I had been searching for. Being a skilled artist. Once I realized that, I shifted my focus. I dedicated myself to becoming a better artist, and my skills skyrocketed.

After a while, I earned the trust to light some shots, and I eventually worked my way up to a Senior Artist position. I found myself in a position where I could help others avoid the same mistake I made.

Philosophy For Training 3D Artists

So, I co-founded the Academy of Animated Art and began working with students, teaching them the craft of being an artist in animated films. Of course, we discussed software, but the emphasis was always on the artistry. I can't count the number of times I repeated, "The software you're using doesn't matter. Focus on the craft. Train your eye to create compelling images regardless of the software. Train your eye to analyze an image, recognize its strengths and weaknesses, and make the adjustments to elevate it to its fullest aesthetic potential."

Besides, software comes and goes. I spent so much time mastering Shake and Mental Ray, but guess what? Apple discontinued Shake's development in 2009, and when was the last time you heard of a studio using Mental Ray?

Software is always evolving, but if you have the artistic sensibilities to create a strong image, that will never go out of style.

Now, what about the world of AI?

But let's talk about the present, where Generative AI reigns. Surely, things must be different now. It's all about text prompts, right? As long as you know how to craft those prompts, you can effortlessly produce beautiful images. Isn't that the case?

I actually fell into that line of thinking for a while. I studied how different people used text prompts and even considered taking a course on writing them. Then I realized I again had fallen for the same trap off being software focused.

Besides, do we really believe that text prompts are the be-all and end-all? Do we genuinely think that with all the development and funding pouring into Generative AI, someone won't create a better user interface than typing long lines of cryptic text? I mean, Midjourney can do some amazing things, but do we honestly think it will continue existing solely as a text interface on a Discord server? That's just bananas. I don't think learning to write great prompts will be a skill that matters six months from now.

So, where does that leave us? Even in this world of rapidly generated images, I still strongly encourage you to chant the mantra:

The software doesn't matter. It's your artistic eye that matters.

Because no matter how quickly you can generate images, if you can't discern a good one from a mediocre one, what's the point? Making more of something doesn't automatically mean you're doing it better.

Let's take a look at photography.

We act as if this rapid explosion of image-generating ability is a new phenomenon. Come on, folks, don't you remember? We used to buy film, load it into our cameras, shoot our 24 or 36 shots, then drop them off to be developed. We'd return to pick up the printed pictures and potentially buy more film to repeat the process. I can't be the only one old enough to remember that, right?

And now, here we are, each of us carrying incredible cameras in our pockets, capturing an almost limitless number of photos. We can upload them to Instagram, quickly manipulate them, and apply filters that used to require harmful chemicals and hours, days, even weeks to produce. And all of this is just a touch away.

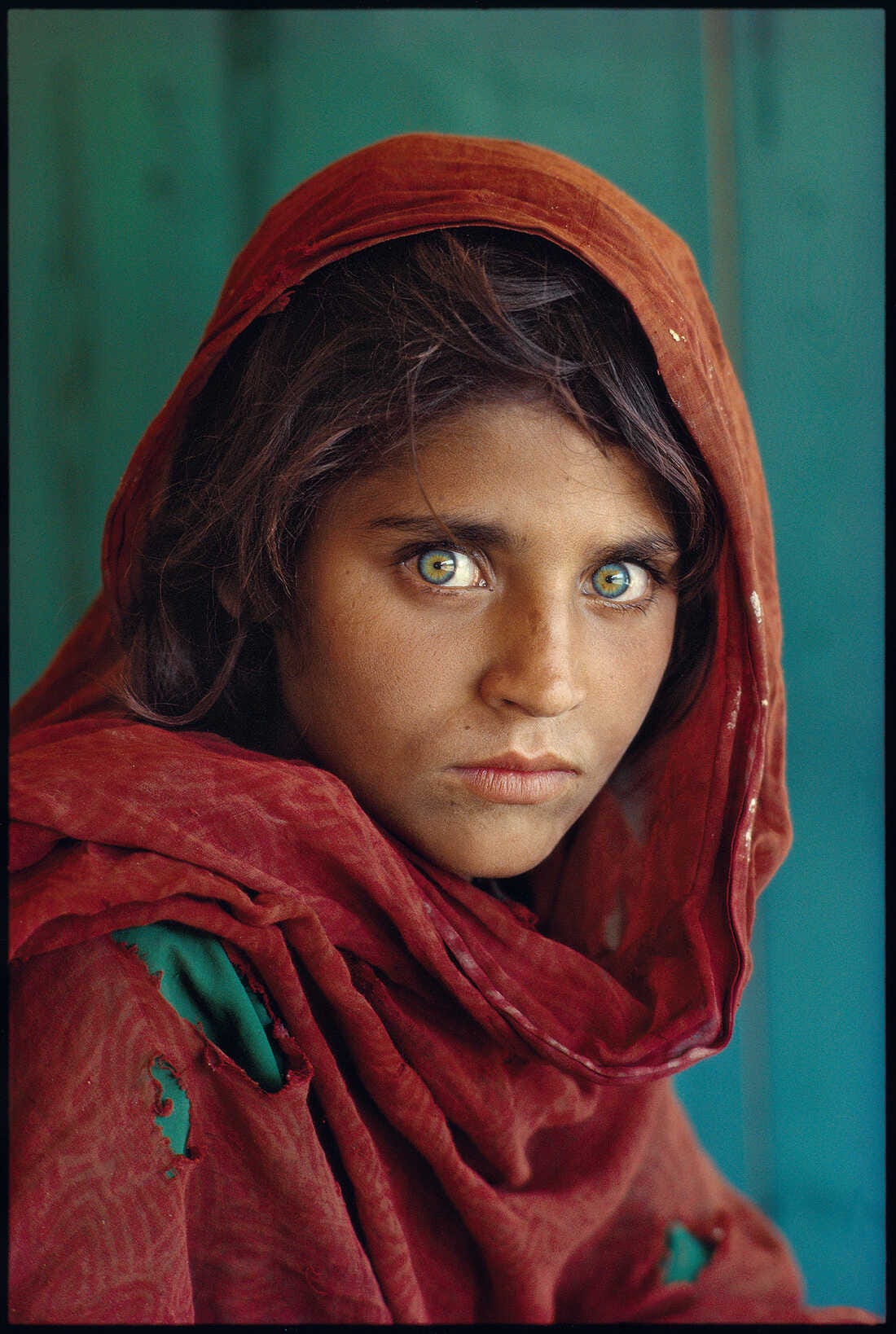

But did this explosion of photography lead to better pictures being taken by everyone and all photographers replaced? No.

Sure we have more images now, but do we have more compelling, noteworthy images than before? Maybe a little but definitely not enough to replace photography as a profession. It still takes skilled, trained, elite artists to create the best images out there. Not all of us have the skill to be National Geographic photographers. It's not because we lack the time or money to travel; it's because those photographers are incredible. They would be able to capture stunning shots with any piece of equipment. Most people simply don't possess that level of skill.

Next steps.

In this world of rapidly creating images, I highly encourage you to keep repeating the mantra:

The software doesn't matter. It's your artistic eye that matters.

Don't get caught up in text prompts or chasing the next technological trend. Instead, focus on developing your artistic eye. Train yourself to understand light, color, composition, emotion, mood, and all the other elements of good visual storytelling.

That's exactly what I aim to provide for you in some upcoming newsletters.

In the next few articles, I will delve into specific aesthetic goals. We'll explore what makes a good image, how to evaluate it, how to improve it, and the process of successfully creating compelling images.

I may take a break now and then to write about something topical that inspires me, but get ready to exercise your artistic eye. Artistic workouts are coming!

3D News of the Week

A roundup of interesting 3D related news you may have missed this week.

Stability AI Releases Stable Animation SDK - 80.lv

Google partners with Adobe to bring art generation to Bard - techcrunch.com

Autodesk ships Maya 2024.1 and Maya Creative 2024.1 - cgchannel.com

Google Introduces Starline - A 3D Remote Meeting Solution - YouTube.com

What is good 3D rendering and why does it matter for fashion? - fashionunited.uk

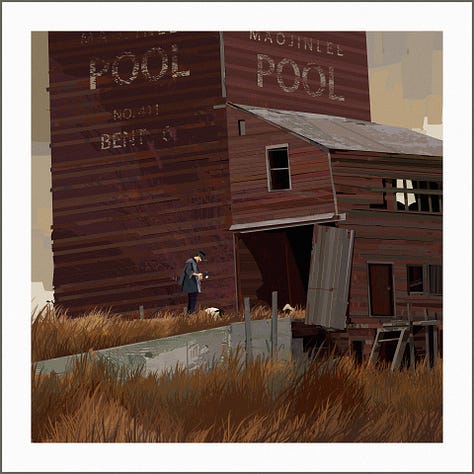

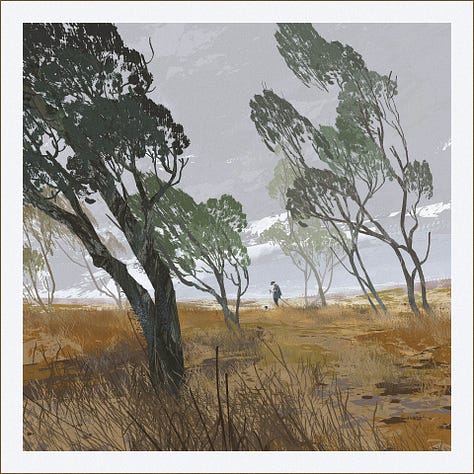

Artist of the Week

3D Tutorials

3D Job Spreadsheet

Link to Google Doc With A TON of Jobs in Animation (not operated by me)

Michael Tanzillo has been a Senior Artist on animated films at Blue Sky Studios/Disney with credits including three Ice Age movies, two Rios, Peanuts, Ferdinand, Spies in Disguise, and Epic. Currently, Michael is a Head of Technical Artists with the Substance 3D Growth team at Adobe.

In addition to his work as an artist, Michael is the Co-Author of the book Lighting for Animation: The Visual Art of Storytelling and the Co-Founder of The Academy of Animated Art, an online school that has helped hundreds of artists around the world begin careers in Animation, Visual Effects, and Digital Imaging.

www.michaeltanzillo.com

Free 3D Tutorials on the Michael Tanzillo YouTube Channel

Thanks for reading The 3D Artist! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. All views and opinions are my own!

I’m really looking forward to the series.

And also - “Come on, folks, don't you remember? We used to buy film, load it into our cameras, shoot our 24 or 36 shots, then drop them off to be developed. “ 😆 Good times.